Dr. Huang has been with Taiwan root since its inception. He participates in almost every medical mission- doing work in Taipei’s mountain regions once or twice a month, and traveling abroad 4-5 times a year. Dr. Huang also volunteers at the HIV dental clinic in Taipei and has a private dental practice in Pan-chiao.

RM: Why do you do this kind of work?

DH: I like the feeling of accomplishment I get from this, and I realize that it is just the natural thing for me to do. Through this work I have learned to see things from outside of my Taiwanese perspective and have taken on a more global view of the world. I guess the most important thing for me is the satisfaction and, well, joy I get when I am able to connect with people who are so different and actually help them when they are in need.

RM: How did you start going on medical missions? Wasn’t it difficult to balance this work with the demands of your dental practice?

DH: Well, I was invited. Some other doctors were already doing it, and they asked us (what became Taiwan Root) to come along. Of course, at the initial stage we were all pretty hesitant about undertaking such an arduous task, but we kept encouraging each other, and eventually got it going. The most important thing for someone interested in doing this is to make sure that when you start you have a stable environment that will support you through the beginning without too many distractions. I suppose the trick for me was to not do too much too fast. When I first became involved with Taiwan Root, I told myself that I needed some type of goal. I decided that I would do this type of volunteer work for at least one year so I could be sure that it was suitable for me. I also needed the time to work out the volunteer work with my work schedule.

RM: How many teeth you have pulled in one day?

DH: Well, when we were in Africa I pulled around 50 or 60 teeth from about 100 different patients in a day of medical service. In Africa, pulling teeth is more difficult than other places. African's teeth generally have roots that grow deep into the jaw, and it can be really hard to extract an entire tooth, especially if the tooth has fused to the jawbone.

RM: What was your impression of the people in the Amazon? How did you feel about their situation?

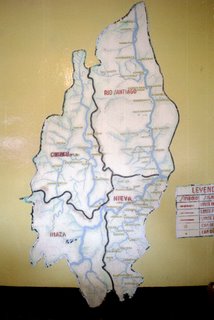

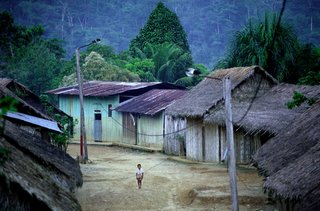

DH: I guess I could answer this question in a number of different ways. We were able to help them solve some of their medical problems, and in some ways meet their health care needs. I think it is interesting that many people in Taiwan probably would look at the Aguaruna lifestyle and automatically assume that it is an unhappy one. I actually don't think that this is the case at all. For the Aguaruna, closeness with the natural environment, and a community more or less unmolested by "development" is probably the best lifestyle for them. To me, they seemed innocent and optimistic. I saw how joyful and content they were using their traditional methods when hunting or cooking food. While we doctors, or other outsiders, try to help them in a way which we think is beneficial, they might just want to maintain their own culture and lifestyle without being disturbed. At the same time, I feel that politically they are in an inferior position, which may have a lot to do with the way others view their traditional way of living. From what I can tell, the Aguaruna are treated unfairly by the people in power in Peru. In some ways, they are deprived of their human rights. They suffer from such a gross shortage of medical services, while the army has built well-equipped hospitals and bases. We Taiwanese, as well as other people from around the world should become more aware of such things and try to help as much as we can.

RM: What are some of the differences you saw between people in Taiwan and the people in the Amazon?

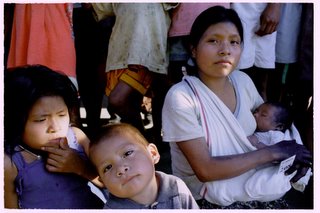

DH: There was one thing that really surprised me. I noticed that the way that parents treat their children in the Amazon is similar to the American style of parenting in the way that they connect with their children. For example, while we were searching for cavities or extracting teeth the children were so nervous, this was their first visit to a dentist, and they were always crying and making a fuss. The parents weren’t impatient at all; instead, they did their best to comfort their children. They would spend as long as two hours asking the children what they were scared of, patiently explaining that we wanted to help, that they weren't in trouble or being punished. The amount of interaction parents had with their children was quite impressive. I can only imagine how angry Taiwanese parents would be if their children did the same thing at my clinic in Pan-chiao. When you look at this simple interaction between parents and children, it is easy to see the differences in socialization between Taiwan and Peru. Because of these differences we must also take care to recognize that there must be different methods of treatment as well. In the Amazon, children will eventually trust us to an extent, but won't submit to us.

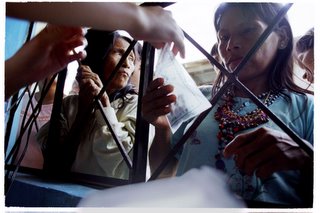

RM: Speaking of different treatment methods, what type of clinical differences between your patients in Taiwan and those in the Amazon? How do treatment methods change when you are practicing "flashlight dentistry"?

DH: It is very comfortable and convenient to treat patients in Taiwan, while it is strenuous and inconvenient to do so in Peru. All of the equipment is so sophisticated and delicate in Taiwan, while all of the equipment in Peru was very crude. As you said, we even had to use flashlights to perform basic check-ups and treatment. Because of this, we generally spend twice as much time treating a patient when we are in developing countries. It can be quite a challenge.

We have found that the structure of people's teeth and oral cavities vary from region to region. Every group of people has its own unique lifestyle and diet. The people in more developed countries generally have more decay because they eat more sugar, while those from the developing world have less decay but a higher rate of periodontal disease. For instance, in the Amazon people's teeth had a lot of wear from grinding- because their food is rougher and they need to chew more. All of them are different from the cavities I treat in Taiwan.

RM: What is the most beneficial part of these medical services? How has your view of these medical missions changed from your first mission until now?

DH: My first overseas medical mission was in refugee camps in Macedonia. Before I left I had no idea what I was going to do, how I was going to practice dentistry, or even if the refugees needed dental care at all (laughing). After we arrived, it turned out that they needed dentists more than most other places. The country is somewhat developed, but the political situation in Macedonia caused the refugees to have to constantly drift around, sometimes without even spare clothes, let alone a toothbrush. During our two week service at the camp, thousands of refugees lined up to see Taiwan Root dentists. It was even a bit of a surprise to the UN and MSF, and we all felt proud that we had this chance to help people in need. We would have never known what the situation in Macedonia was like if we hadn't gone there to see for ourselves.

I feel grateful that I have been able to step out of my own culture and see a totally different world, while at the same time using my skills to help people. I guess the most beneficial part of these medical services is being able to bring medical care to people who are often forgotten by the rest of the world. We also bring the stories and conditions of these people back from the “secret places” we visit. This lets people understand the lives and conditions of people totally different from them.